What Is a Cancer Commons Options Report?

Curious Dr. George

Cancer Commons Contributing Editor George Lundberg, MD, is the face and curator of this invitation-only column.

Lola Rahib, PhD Lead Scientist in Pancreatic Cancer at Cancer Commons

As a Cancer Commons Scientist, Lola Rahib, PhD, helps cancer patients and caregivers navigate treatment. Some of these patients receive a Cancer Commons Options Report. Here, our Curious Dr. George asks Dr. Rahib to share what goes into each Options Report.

Curious Dr. George: Cancer Commons provides advanced cancer patients who seek information with additional options for them to consider, all free of charge. What does a typical Cancer Commons Options Report consist of and look like?

The first page of the report contains information about the patient, including patient goals, molecular alterations, and a short case summary. Patient goals may include treatment and quality of life goals, ability to travel for treatment, and any other life goals or preferences the patient or their caregiver shares with us. The molecular alterations section is extracted from the patient’s molecular profiling report(s). Molecular profiling is an important consideration, as it can guide treatment. The short case summary gives a brief overview of the patient’s diagnosis and treatment history.

The report also contains a comprehensive, personalized case summary detailing the patient’s cancer history. The personalized case summary is created by reviewing the patient’s medical records, and includes information about the patient’s diagnosis, pathology, treatment history, treatment response, genomic sequencing, and other testing as available. This detailed summary is found at the end of the report and may be helpful for patients to take with them to appointments, especially if they are visiting with a new physician.

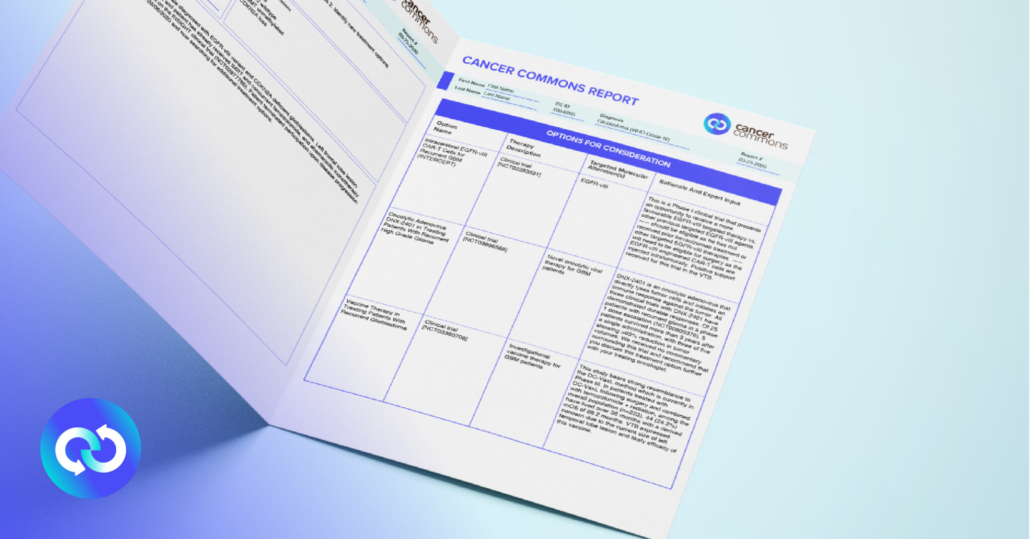

The detailed summary is used to generate personalized therapeutic options, including investigational therapies, clinical trials, off-label combinations, and testing modalities such as next generation sequencing, liquid biopsies, and other diagnostics. These options are presented in a table format with therapy descriptions and scientific rationale. Molecular targets for specific treatment options are indicated when appropriate.

Feedback and consensus from a Virtual Tumor Board is also provided when applicable. Currently, Cancer Commons has a Virtual Tumor Board program for brain and pancreatic cancer patients. The Virtual Tumor Board program allows Cancer Commons to present a patient’s case to nationally recognized experts. The panel performs a comprehensive review of the patient’s diagnosis, treatment history, molecular profiling, genetics, and other relevant information. Based on this information they discuss and provide feedback on treatment options including clinical trials, and any further diagnostics and evaluations. This feedback is provided in a summary along with the detailed treatment options.

The final decision regarding tests and treatments is always up to the patient and their care team. We encourage patients to discuss these options with their treating oncologist.

We capture decisions and rationales, and patients’ progress is monitored over time. This supports learnings and insights from every patient. Our artificial intelligence platform uses the Virtual Tumor Board’s recommendations, treatment decisions, and clinical results to get smarter. Our goal is to continuously learn from every patient’s experience and use that knowledge in real-time to help the next patient.

Dr. Rahib can be reached at lola.rahib@cancercommons.org.

***

Copyright: This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

A Q&A with crisis communication expert

A Q&A with crisis communication expert